Extraordinary career of an extraordinary man

New article on the young Karl Ziegler published in the journal Angewandte Chemie

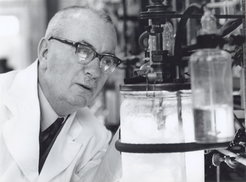

Karl Ziegler is considered one of the most important chemists of the 20th century. However, little is known about the Hesse-born man's youth and early years as a scientist. A new article by Christoph Kießling in the journal Angewandte Chemie now sheds light on the young Ziegler.

Karl Ziegler, who was Director of the Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung from 1943 to 1969, is considered one of the most important chemists of the 20th century. He is known to many for the Nobel Prize he received in 1963 together with Giulio Natta for developing the process for the synthesis of low-pressure polyethylene. But what kind of person was Karl Ziegler? How did it come about that the man from the tranquil Helsa, who always aspired to a career as a university professor, finally ended up in Mülheim to head a Kaiser Wilhelm Institute?

This question has now been investigated by the historian and former head of the historical archive of the MPI für Kohlenforschung, Christoph Kiessling. He has published his findings in the journal Angewandte Chemie. The fact that a historical essay is appearing in a journal for chemists can certainly be described as unusual.

In his work, Kiessling paints the picture of a scientist who was extraordinary in every respect. Ziegler's outstanding career was already apparent at a young age. In 1915, at the age of just 16, he completed his schooling with his university entrance qualification. After a year as a war nurse in Galicia, he began his chemistry studies in Marburg in 1916. One year later, he passed his first association exam, which was unusually fast. According to his own later account, the young man had simply skipped the first two semesters.

Making a name among his peers

In 1920, after he had been drafted into military service in the meantime, Ziegler submitted his dissertation. This was followed by postdoc years, his habilitation and numerous publications, with which he made a name among his peers. In 1928 Ziegler received an associate professorship at the University of Heidelberg.

Under the National Socialist regime, however, Ziegler's career stalled. From various letters and reports, Christoph Kiessling has gathered that the regime was concerned that Ziegler might have a negative influence on students in the Nazi sense. He had shown no signs of “working to rebuild German universities in the National Socialist spirit”.

And so Ziegler was denied a professorship not only in Heidelberg, but also at other faculties. Nevertheless, it was known that he was also regarded as a capable scientist abroad. In 1936, he took up a guest professorship in Chicago. There was “a risk of emigration to America, and we must hold on to such people,” according to an opinion by the Gaudozentenbund leader Ernst Krieck.

More research, less teaching

And after Ziegler had been offered a position at the University of Halle in 1938, negotiations began in 1942 to win him as successor to Franz Fischer, the director of the KWI für Kohlenforschung in Mülheim. Here, according to the National Socialists' idea, he would continue to conduct research on German soil, but without gaining too much influence over students. After all, the focus of the KWIs had always been on research and less on teaching.

Ziegler accepted the offer in Mülheim – but only under certain conditions. He wanted to expand the institute much more than it had been before, “...on the one hand in the direction of general and synthetic organic chemistry, and on the other hand in the direction of a stronger consideration of physical and physical-chemical aspects and research methods.”

In his essay, Kiessling also outlines Ziegler's further career and speaks overall of “the image of a man whose later fame was shaped by a long prehistory that brought him many disadvantages, particularly during the Nazi era”. The fact that he did not politically align himself with the regime sets him apart from many others and emphasizes a premise that he always set as his own standard: to convince through scientific excellence.